In early August I visited the first archive, located in Oleiros (A Coruña), not far from my base of operations. It was my first experience undertaking this type of research, and I didn’t know what to expect. I arrived in the small archive, hidden on the side of a building in Plaza de Galicia [Galicia Square] and I was welcomed by the person in charge, who interviewed me briefly to know about my research, what would I do with the material I would find, etc. Next, she sat me at a desk not far from her office and brought me a Register Book which covered the years 1929 to 1944, and a typed document, signed by a man called Manuel Zapata. As the archivist explained to me, Zapata was a retired teacher living in New York, although originally from Oleiros, who had spent some time at the archive years ago, conducting a research similar to mine. I was not allowed to make copies of this document, which Zapata had posted to the archivist upon his return to the US, but I could read it and take notes. The Register Book recorded passport applications in which the future migrants specified where they were travelling to: many of them were planning to go to Latin America (Buenos Aires, especially), but there was also a good number of people who wanted to go to New York (great!). The later entries also included the applicants’ profession: most men were sailors and most women were dedicated to ‘sus labores’ [home tasks, i.d. housewives].

Zapata’s work was very useful. Although it was primarily a ‘volcado’ [dump] of the information included in the books I had next to me, the author of the document also made some personal comments, created statistics, and provided information about some of the people recorded in the Register. He begins by stating that ‘nos incumbe recordar y darle sentido a aquellos hijos de Oleiros que se vieron obligados a marcharse de su “paraíso” por razones ajenas a su voluntad, la gran mayoría para jamás poder regresar’ [we are concerned with remembering and giving a meaning to those sons of Oleiros who were forced to leave their ‘paradise’ for unwanted reasons, in most cases to never return]. From the emotional tone of his words, it became quite obvious that he could have been one of this people that he was researching decades later. This was confirmed when I found an entry from 1938 in the Register Book, with a photo of an eight-year-old Manuel Zapata.

One of the interesting aspects Zapata points out in his study is the difficulty to know exactly how many Galicians migrated from Oleiros to the United States. The records (both in Galicia and New York) would leave out a great number of people who went either via other ports such as Southampton, Lisbon and Le Havre (which were stated as their final destination in the Register) or arrived illegally in the US, usually after a stay in Latin America. He argues that,

a partir de la ley de inmigración McCarran de Estados Unidos, en 1924, la cual le otorgó una cuota mínima a España de 250 personas anuales, muchos optaron por la entrada de forma clandestina, yendo primero a Cuba y allí embarcando de fogoneros o engrasadores para luego saltar a tierra en el primer puerto que tocaba en Estados Unidos. He conocido personalmente a muchos de estos gallegos.

[after the McCarren Immigration Act in 1924, which established a quota of 250 Spaniards per year, many chose to enter the country illegally, going to Cuba first and enrolling a ship as stokers or lubrication servicers so they could disembark at the first US port they got to. I have met many of these Galicians.]

Although Zapata refers to the wrong law (the McCarren act was passed in 1952 and the 1924 Inmigration Act was called Johnson–Reed Act), his study seems right in suggesting that many more Galicians arrived in New York than those officially recorded in Ellis Island and registered at the Spanish Consulate.

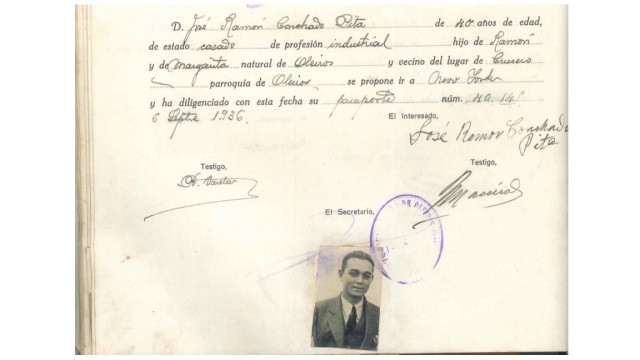

Another difficulty Zapata encountered in his study was the fact that many migrants from Oleiros applied for a passport in A Coruña (so I also had to look into this city’s archive!) and others might have used someone else’s identification (from a relative, for example), especially if they were in danger of being killed by Francoist supporters during the Spanish Civil War. In this regard, he also mentions the case of María de las Nieves Sánchez, who requested a passport twice, on 8/09/1936 and on 21/01/1938. She didn’t travel in 1936 because her husband, José Ramón Conchado Pita, was arrested by the Fascists. He was freed soon afterwards, but fearing to be taken for a ‘paseo’ [a walk, meaning a secret execution], he left for New York via Portugal. His wife and children reunited with him in 1938. I looked a bit into the case, and found out that there is a file with the name ‘Ramón Conchado Pita’ at the ‘Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica’ [Centre for the Document Archive of the Historical Memory] (Salamanca), in which he seems to have been accused of being a Communist and a freemason (regarded by the Francoists as ‘enemies’ of Spain).

In my first visit, the connections between Galician migration to New York and the historical memory of the war systematically erased by the subsequent dictatorship started to emerge. The archivist also mentioned the case of Tomás Arévalo, the Republican mayor of Oleiros in 1936, who applied for a passport, although it isn’t known whether he managed to eventually use it. Like many of the council members at the time, they disappeared without a trace at the beginning of the war. Quite possible, they were taken for a ‘walk’…

I requested to take a copy of some of the entries of the Register Book, which the archivist kindly sent me by email a few days later. I decided to choose some cases that were representative of the most common profile of the migrant to New York (sailors, etc.) but also other cases with a political background like Conchado Pita’s.

After leaving the archive, I became quite curious about this Manuel Zapata. I did some searches but could only find very limited sources about him. In a blog, it is said that he was a teacher at William Cullen Bryant High School, a veteran of the Korean War, a historian who documented New York’s Spanish neighbourhood and published a study entitled Spain and Spaniards in the History of the United States, and was considered as ‘el Padre Cultural de la Emigración Hispana en los Estados Unidos’ [the cultural father of Hispanic emigration to the US]. However, I was completely unable to locate any of his publications (apart from a brief ‘History’ of the Casa Galicia [House Galicia] of New York). Curiously enough, the scholar who had studied the migration from Oleiros to New York had also become part of my study. However, it would take me around a month to know more about him, this time in a different archive.