‘A crowd of starving, desperate people dressed in rags began to walk towards the border. Women, children, old people… […] It was horrible, it was a beaten people, without a horizon. In that moment, I had a breakdown. Everything that I thought my life could have become was vanishing forever’ (Público 12/09/2015).

This is the testimony of Alejandra Soler, one of the survivors of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), who after the fall of Catalonia at the hands of the fascist forces at the end of the conflict, crossed the Pyrenees seeking to find refuge in France. This migratory movement, called ‘la Retirada’ [the Retreat] brought around 500.000 Spaniards to their neighbouring country: ‘doscientos cincuenta mil militares se unen a los diez mil heridos, ciento sesenta mil mujeres y niños, y sesenta mil civiles que habían llegado ya desde enero’ [250,000 soldiers plus 10,000 injured, 160,000 women and children and 60,000 civilians who had already arrived since January] (Rafaneau-Boj quoted in Simón Porolli 2011: 58). The destiny of most of these refugees was the ‘concentration camps’ (term used by the French authorities at the time)[i] improvised in the south of the country. The French authorities were in fact reluctant to welcome them from the start: ‘apenas cruzaban la frontera, se les instaba a volver atrás o alistarse en la Legión Extranjera’ [as soon as they crossed the border they were either pressed to go back or to enlist the Foreign Legion] (Dreyfus-Armand 2003: 35).

The refugees were also used by the new Francoist government (swiftly accepted as legal both by France and the UK, which had signed a non-intervention agreement during the Spanish war) to pressure their French counterpart to send the gold that the Republican government had deposited in Banque de France to Spain. Franco’s regime refused to accept any returning refugees until those nearly five and a half thousand Francs were also returned to Spain (Dreyfus-Armand 2003: 35-36). Many of those who went back were judged, following the new law of ‘political responsibility’, for acts against the Francoist side during the war or for their involvement with the Republic: in post-war Spain there were also concentration camps, although far worse than the French ones (see Rodrigo 2005).

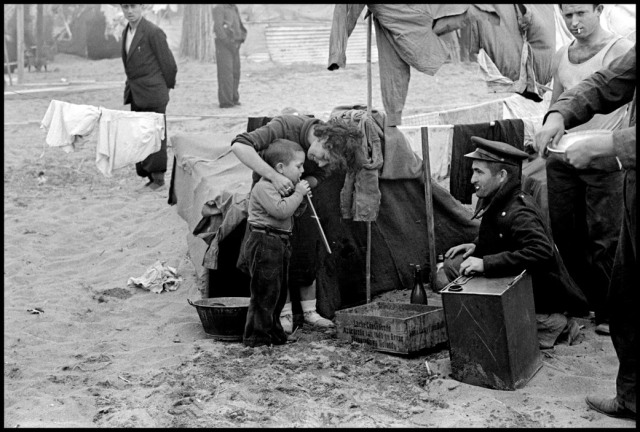

In France, Spanish refugees had to endure inhumane conditions: families were separated, food and water were scarce, hygiene was almost non-existent… The photographer Robert Capa, who visited the camp located at the beach in Argelès-sur-Mer (which held around 75,000 Spanish men) called it ‘a hell on the sand’. (Whelan 1985: 158). His biographer Richard Whelan describes it as follows:

the camp [was] surrounded by barb wire and patrolled by mounted Senegalese soldiers who were uncomfortably reminiscent of Franco’s cruel Moors […] The French, who had not prepared for such a massive influx of refugees, had barely begun to build barracks when the first men arrived. Now, more than a month later, most of the men still had to improvise their own tents and straw huts. Such shelters, however, gave insufficient protections against the wind-driven sand that inflamed eyes and irritated skin, causing an epidemic of skin sores. To make matters worse, there was no running water, only blackish water from holes dug in the sand. (1985: 158)

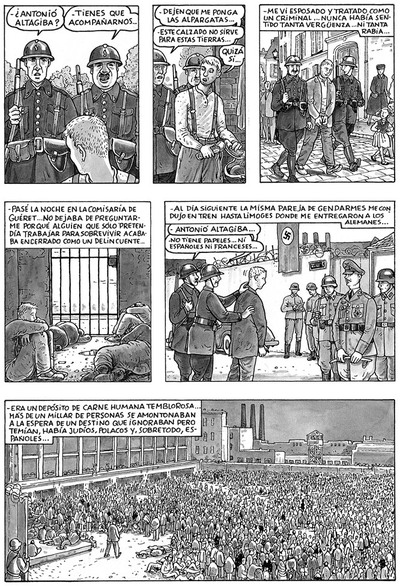

Most Galicians escaping from the war went directly to Latin American countries. However, the historian Xosé M. Núñez Seixas points out that ‘uns 1.320 galegos, como mínimo, pasaron polos campos franceses’ [at least some 1,320 Galicians stayed at the French camps] (2016: 128). One of them was the writer Rafael Dieste, who stayed in Saint Cyprien’s camp. The British writer Nancy Cunard visited the camp in 1939 as press correspondent. In one of her chronicles she wrote that ‘había internados unos quinientos escritores, artistas y músicos, “insultados por los guardias”, “muertos de hambre”, “encarcelados por las bayonetas de los senegaleses” y “obligados a dormir al aire libre, sin nada en el suelo, expuestos al gélido viento”’ [there were around five hundred writers, artists and musicians ‘insulted by the guards’, ‘starved’, ‘incarcerated by the bayonets of the Senegalese soldiers’ and ‘forced to sleep in the open, without anything on the floor, exposed to the freezing wind’]. Cunard also provides a list with some of their names. One of them is Dieste (Cabañas Bravo 2006: 103-104). The hardship endured by the refugees in Saint Cyprian has been depicted in the comic book El arte de volar [The art of flying] (2001) by Antonio Altarriba (writer) and Kim (artist), inspired by the real experience of Altarriba’s father.

Although not as famous as Dieste, another Galician confined in the French camps was Manuel García Gerpe, a lawyer from Ordes (A Coruña), member of Izquierda Republicana (Republican Left) and miliciano who fought against Franco in Madrid. García Gerpe narrated his horrendous experience at the camps in Alambradas, mis nueve meses por los campos de concentración de Francia [Wire Fences, my Nine Months at the French Concentration Camps], published in Buenos Aires in 1941. As Víctor Fuentes (2000: 76) points out in his study of the narrative produced by Galician exiles, the book describes ‘as tráxicas e patéticas escenas do éxodo: nenos que morren á intemperie nos brazos das súas nais, familias desfeitas vagando polos campos franceses, poñendo anuncios para indagar o paradoiro doutros membros perdidos da familia’ [the tragic and pathetic scenes of the exodus: children dying out in the open in their mother’s arms; broken families wondering the French countryside, using ads to try to find out the whereabouts of missing members]. Fuentes (2000: 75) quotes the opening of García Gerpes text:

Acampamos en aquellas tierras empapadas de agua, al fondo de la estribación pirenaica, ‘Le Canigou’, cuyas cumbres, recubiertas de blanca nieve, exhalaban oleadas de frío. Se sucedieron los días… y las semanas. Allí entre el frío, la humedad, la nieve, el hambre, la persecución, el abandono y la tristeza, luchamos con la muerte. Muchos cayeron en esta terrible lucha: algún día ascendió a cincuenta el número de muertos.

[We camped in those damp lands, at the end of the foothill ‘Le Canigou’ in the Pyrenees, whose peaks, covered in white snow, exhaled waves of cold. The days went by… and so did the weeks. There, among the cold, the humidity, the snow, the hunger, the persecution, the abandonment and the sadness, we fought against death. Many dropped in such terrible fight: some days the number of deceased went up to fifty.]

On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, the situation of the Spanish refugees did not pass unnoticed to those exiles who had managed to leave Europe. In New York, the Sociedades Hispanas Confederadas [Confederate Hispanic Societies] (SHC) (which comprised more than one hundred Spanish anti-fascist societies, such as the Frente Popular Antifascista Gallego [Antifascist Galician Popular Front]) had sent humanitarian aid to the Republican army during the war. Once Spain was under Franco’s control, they focused their efforts on helping those who were stranded in France. Núñez Seixas states that ‘foi salientábel a actividade desenvolvida polo Frente Popular Antifascista Gallego (FPAG) de Nova York’ which ‘contribuíu a fornecer fondos para a evacuación a América de refuxiados galegos e españois nos campos de internamento franceses’ [the activity carried out by the FPAG was especially important as it contributed to gather funds for the evacuation to America of Galician and Spanish refugees who were at the French camps]. However, as Núñez Seixas continues,

dos cartos enviados ao SERE [Servicio de Evacuación de Refugiados Españoles] polo FPAG non todo se destinou a repartriar exiliados galegos cara a México e a República Dominicana, como era o propósito de Castelao e outros dirixentes do Frente, quen razoaban que, se a maioría dos españois residents en EUA que contribuían á causa republicana eran galegos, de xustiza era que unha boa parte dos seus recursos se destinasen aos refuxiados galegos en Francia. (2016: 104-105)

[not all the money sent by the FPAG to the SERE [Service of Evacuation of Spanish Refugees] was used to repatriate Galician exiles to Mexico and the Dominican Republic, as it was the aim of Castelao and other leaders of the Front, who argued that most of the Spaniards living in the USA who contributed to the Republican cause were Galicians, and therefore, it was only fair that a great part of their resources was sent to help Galician refugees in France.]

As shown by his private correspondence, Castelao actively campaigned in New York to bring as many Galicians as possible from France to America (Rodríguez Castelao 2000: 291-292). Nevertheless, these funds were not always managed with transparency. This issue, together with the increasing internal divisions inside the SHC and the way they were managed, led the Galician artist and politician to have a rather negative view of the Spanish exile (Núñez Seixas 2016: 169). Despite Castelao’s disappointment, New York was the first destination in the American continent for a number of Galician exiles. Nancy Pérez Rey points out that the Galician Xosé Castro, Secretary General of the SHC, was sent to France to facilitate the relocation of the refugees to Mexico. Many of them were Galicians (2001: 606-7). Some exiles, like Emilio González López, could avoid the camps; however, they were still harassed by the French police, as he explains in his private letters, where he also says: ‘estos días han llegado a París dos representantes de las Sociedades españolas de New-York. Traen la oferta de aquellas sociedades de pagar 1000 pasajes de españoles con destino a Méjico’ [recently, two representatives of the Spanish Societies from New York have arrived in Paris. They bring the offer of paying a ticket to Mexico for 1,000 Spaniards] (quoted in Gómez Rivas 2009: 163). González Lopez was one of them, although he remained in New York for the rest of his life, where he worked as university lecturer.

In 1939, thousands of Spaniards, some of them Galicians, who were escaping death in their own country, found themselves in a ‘jungle’ in the south of France. More than 70 years later, history repeats itself in Calais. Different protagonists but the same tragedy. Europe should learn from its past.

Works cited

Caamaño, Javier (2015). ‘Los españoles que huyeron de la guerra y acabaron en otra pesadilla’. Público 12/09/2015. http://www.publico.es/politica/espanoles-huyeron-guerra-y-acabaron.html

Cabañas Bravo, Miguel (2006). Rodríguez Luna, el pintor del exilio republicano español (Madrid: CSIC).

Dreyfus-Armand, Geneviève (2003). ‘Los movimientos migratorios en el exilio’. In El exilio republicano en Toulouse, 1939-1999, ed. by Alicia Alted and Lucienne Domerge (Madrid: UNED), 29-52.

Fuentes, Víctor (2000). ‘Arredor da narrativa galega no exilio’. Grial 145: 71-87.

Gómez Rivas, Isabel (2009). ‘Noticias dos primeiros momentos do exilio de Emilio González López a través da súa correspondencia con Luis Jiménez de Asúa’, Estudos Migratorios: Revista Galega de Análise das Migracións II(1): 153-166.

Núñez Seixas, Xosé M. (2016). O soño da Galiza ideal. Estudos sobre exiliados e emigrantes galegos (Vigo: Galaxia).

Pérez Rey, Nancy (2001). ‘Panorama do exilio republicano galego en Nova York’. In Actas do Congreso Internacional o Exilio Galego (Santiago de Compostela).

Rodrigo, Javier (2005). Cautivos: campos de concentración en la España franquista, 1936-1947 (Barcelona: Crítica)

Rodríguez Castelao, Alfonso Daniel (2000). Obras. Epistolario. Volume 6, ed. by Xosé M. Núñez Seixas (Vigo: Galaxia)

Simón Porolli, Paula (2011). Por los caminos de la palabra. Exilio republicano español y campos de concentración franceses: una historia del testimonio. PhD Thesis. Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona.

Whelan, Richard (1985). Robert Capa: a Biography (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press).

[i] ‘En el contexto francés de 1939 […] el objetivo del gobierno galo consistía en diferenciar el “campo de concentración” del “centro penitenciario”, entendido como un espacio en el que se impartían castigos disciplinarios […] La realidad demostró que esta elección solamente se mantuvo en el nivel del discurso […] las palabras de los mismos testigos dan cuenta del régimen disciplinario que se estableció en los campos’ [In the French context of 1939 […] the objective of the French government was to differentiate ‘concentration camps’ from prisons, understood as places where disciplinary punishment was inflicted [….] The reality showed that this choice only worked at a discursive level […] the words of the witnesses themselves tell about the disciplinary regime established at the camps] (Simón Porolli (2011: 67).